Quite recently, the news channels were rife with reports of wide scale communal violence and riots in West Bengal as gleaned from several posts on social media website slike Facebook  and Twitter. The fake news went viral on the smartphone messaging platform, WhatsApp too and everywhere opinions flew on what needed to be done and how the State authorities were unable to control the situation. Upon closer inspection it was found that the pictures accompanying these posts were file pictures from the Gujarat riots in 2002. Complaints in this regard were lodged at several police stations in Kolkata. But the damage had been done; a lot of unsuspecting people had already been sucked into this vortex of hate and suspicion. A lot of people actually believed that Bengal was burning and stoked the communal fires in the state. Unfortunately, these are the offline real life consequences of online lies.

and Twitter. The fake news went viral on the smartphone messaging platform, WhatsApp too and everywhere opinions flew on what needed to be done and how the State authorities were unable to control the situation. Upon closer inspection it was found that the pictures accompanying these posts were file pictures from the Gujarat riots in 2002. Complaints in this regard were lodged at several police stations in Kolkata. But the damage had been done; a lot of unsuspecting people had already been sucked into this vortex of hate and suspicion. A lot of people actually believed that Bengal was burning and stoked the communal fires in the state. Unfortunately, these are the offline real life consequences of online lies.

This incident related above is not the first, nor will it be the last. Fake news have been rampant for years, even centuries, long before the advent of the internet, the smart-phone or social media.

One of the earliest instances of fake news was the “Great Moon Hoax” of 1835. The New York Sun published articles about areal life astronomer and a made-up colleague who had observed bizarre life on the moon. The fictionalized article ssuccessfully attracted new subscibers and the paper suffered very little backlash when it finally admitted that the series had been a hoax. Such stories were intended to entertain readers and not to mislead them. Sadly, this is not always the case anymore. The impact of fake news, propaganda and misinformation, now has taken alarming proportions and has been widely scrutinized in the United States since the US election last year.

One of the earliest instances of fake news was the “Great Moon Hoax” of 1835. The New York Sun published articles about areal life astronomer and a made-up colleague who had observed bizarre life on the moon. The fictionalized article ssuccessfully attracted new subscibers and the paper suffered very little backlash when it finally admitted that the series had been a hoax. Such stories were intended to entertain readers and not to mislead them. Sadly, this is not always the case anymore. The impact of fake news, propaganda and misinformation, now has taken alarming proportions and has been widely scrutinized in the United States since the US election last year.

It has been found that fake news actually outperformed real news on Facebook during the final weeks of the election campaign in the US as per an analysis by Buzz feed.

Another famous fake news doing the rounds now and then is that the UNESCO has voted the Indian national anthem the best in the world. While that bit of news would make any Indian proud, the fact of the matter is that it is not true. Another one claimed that Islam is the most peaceful religion as declared by the UNESCO. Again, that may make some people very happy but is equally capable of making some people very angry. In fact things came to such a stand that the UNESCO was compelled to issue a declaration that it does not declare anything!

In 2016 India had over 50 million accounts on the smart phone instant messenger WhatsApp. On the day of demonetization on November 8, 2016 when India released the 2,000-rupee currency bill, the fake news went viral over WhatsApp that the note came equipped with spying technology which tracked bills 120 meters below the earth. The Finance Minister refuted the lies, but not before they had spread to the country’s mainstream news outlets.

There is no question that these fake stories resonate with people. There are people who use these stories for their own gain, or in their own interest (which may be political or financial in nature).

There is no question that people saw these posts, shared them, commented on them, liked them and that they created tremendous velocity on WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter. It is a distressing thing, to say the least. In India, it becomes more of a problem because the lack of education among several sections of the society paves the way for rumour-mongering and belief in the word-of-mouth.

As a father of teenagers, I am well aware of the dangers of the social media and the internet. It is not a world that can be denied either, because a lot of school and college research, projects and homework is done on the internet. The youngsters these days have wide access to all the social media sites, not only Facebook, WhatApp and Twitter and often can be found on Instagram, Snapchat and whatever.

Fake news, the spreading and propagation of fake news is a global problem. Today all over the world, think-tanks and companies are looking for ways to combat the problem with technology.

A growing cadre of technologists, academics and media experts are now beginning the perplexing process of trying to think up solutions to the problem.

“The biggest challenge is who wants to be the arbiter of truth and what truth is,” said Claire Wardle, research director for the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University.

“The way that people receive information now is increasingly via social networks, so any solution that anybody comes up with, the social networks have to be on board.”

Most of the solutions discussed online fall into three general categories: (1) the hiring of human editors (2) crowd sourcing and (3) technological or algorithmic solutions. Let’s have a brief look at these:

(1) Hiring people– especially the number needed to deal with Facebook’s or WhatsApp’s volume of content– is expensive, and it may be hard for them to act quickly.The social network ecosystem is enormous, and commonsense tells us that any human solution would be next to impossible. Humans are also partial to subjectivity, and even an meticulous person can have views which may not be correct and would be in a disproportionately powerful position and open to abuse.

(2) Crowd sourced vetting would open up the assessment process to the body politic, having people apply for a sort of “verified news checker” status and then allowing them to rank news as they see it. This isn’t dissimilar to the way Wikipedia works, and could be more democratic than a team of paid staff. It would be less likely to be accused of bias or censorship because any one could theoretically join, but could also be easier to fool by people promoting fake or biased news by using automated systems on the computer.

(3) Algorithmic or machine learning vetting is the third approach, and the one currently favored by Facebook, who fired their human trending news team and replaced them with an algorithm in 2016. But the current systems are failing to identify and downgrade hoax news or distinguish satire from real stories; Facebook’s algorithm started emitting fake news almost immediately after its inception. Technology companies like to claim that algorithms are free of personal bias, yet they inevitably reflect the subjective decisions of those who designed them, and software engineers and developers can be prone to journalistic errors. Algorithms also happen to be cheaper and easier to manage than human beings, but an algorithmic solution must be transparent.

While the social media websites battle it out and look for solutions, as a parent and a responsible citizen, how do we control the spread and influence of false information through the social media?

Of course, one should never share news on the social media before verifying its content. You probably tell your kids not to believe everything they read. But what you really mean is, “Don’t believe everything you read without verifying it first.” Separating fact from fiction has become a challenging but important step in an online environment where false claims, half-truths, and outright lies are vying for clicks, shares, and likes. Now, the internet’s most popular services are fighting back- and not a moment too soon: As Common Sense’s March 2017 report shows, tweens and teens prefer getting their news from social media sites such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter.

Of course, one should never share news on the social media before verifying its content. You probably tell your kids not to believe everything they read. But what you really mean is, “Don’t believe everything you read without verifying it first.” Separating fact from fiction has become a challenging but important step in an online environment where false claims, half-truths, and outright lies are vying for clicks, shares, and likes. Now, the internet’s most popular services are fighting back- and not a moment too soon: As Common Sense’s March 2017 report shows, tweens and teens prefer getting their news from social media sites such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter.

Until recently, top social and search sites Google, Facebook, and Twitter permitted almost any “news” to grace its platforms. So long as the information didn’t violate their terms of service (bullying or illegal stuff, for example), they relied on users to flag problems or simply speak out their opinions publicly. But some users with malicious or dubious intentions took advantage of this policy to circulate misinformation, influence opinion, make money, and discredit rivals.

Encouraging your children to dig deeper is a smart way to help them develop crucial media literacy skills. Once they start using the internet to share information, research articles, and follow interesting people, they should know how to find reliable information by cross referencing sources, using fact-checking sites, and looking for telltale signs of real and fake news.

Encouraging your children to dig deeper is a smart way to help them develop crucial media literacy skills. Once they start using the internet to share information, research articles, and follow interesting people, they should know how to find reliable information by cross referencing sources, using fact-checking sites, and looking for telltale signs of real and fake news.

Nowadays, there are more tools to help in this effort. See how these online media giants are tackling this challenging topic:

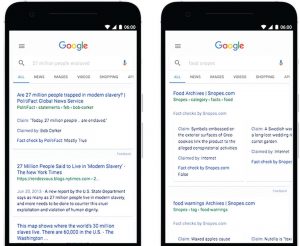

Google’s Fact Check. If your kid is researching information using Google News (either the site or the app), he or she may come across Google’s Fact Check tag. A “fact check” only comes up if the story is controversial, which Google determines in various ways. Google doesn’t label the story true or false, but it encourages users to do more digging.

Facebook’s Disputed Tag. When stories have been flagged as iffy by users or Facebook’s algorithm, Facebook checks with online fact-checkers Snopes and Politi Fact. If the stories are questionable, Facebook puts a “Disputed” note on them. Like, Google, Facebook doesn’t label the story true or false, but adding the Disputed tag should prompt kids to investigate further.

Twitter’s Verified Accounts. Since so many people, including kids, get their news from Twitter, it’s important to know whether tweets are legit or from a hacker, a fly-by-nighter, or another bad actor. Twitter’s Verified Accounts add more stability and accountability in an effort to thwart false information, bullying, and audience manipulation. The company uses a thorough vetting process to determine whether a user is who they say they are and displays a blue check mark next to a verified user’s name.

Unfortunately, human beings have a lot of prejudices: social, cultural, religious and otherwise.

On current evidence, unfortunately, many people feel comfortable when presented by news which doesn’t challenge their own prejudices and preferences–even if that news is inaccurate, misleading or false.

The true solution of these hate and rumour mongering posts is a complex, nuanced and long – term challenge of educating the public about the importance of informed debate– and why properly considering an accurate, rational and compelling viewpoint from the other side of the fence is an essential part of the democratic process. Change can only come with education and an acceptance that we ourselves may have prejudices which we need to discard. That is real change, change that can make a difference.

In the words of Claire Wardle, “How do we bring people together to agree on facts when people don’t want to receive information that doesn’t fit with how they see the world?” THAT is something to think about.

Amitesh Banerjee

Senior Advocate,

Senior Standing CounselState of West Bengal